Inside "She" – A Cathedral: Reclaiming the Female Form, Then and Now

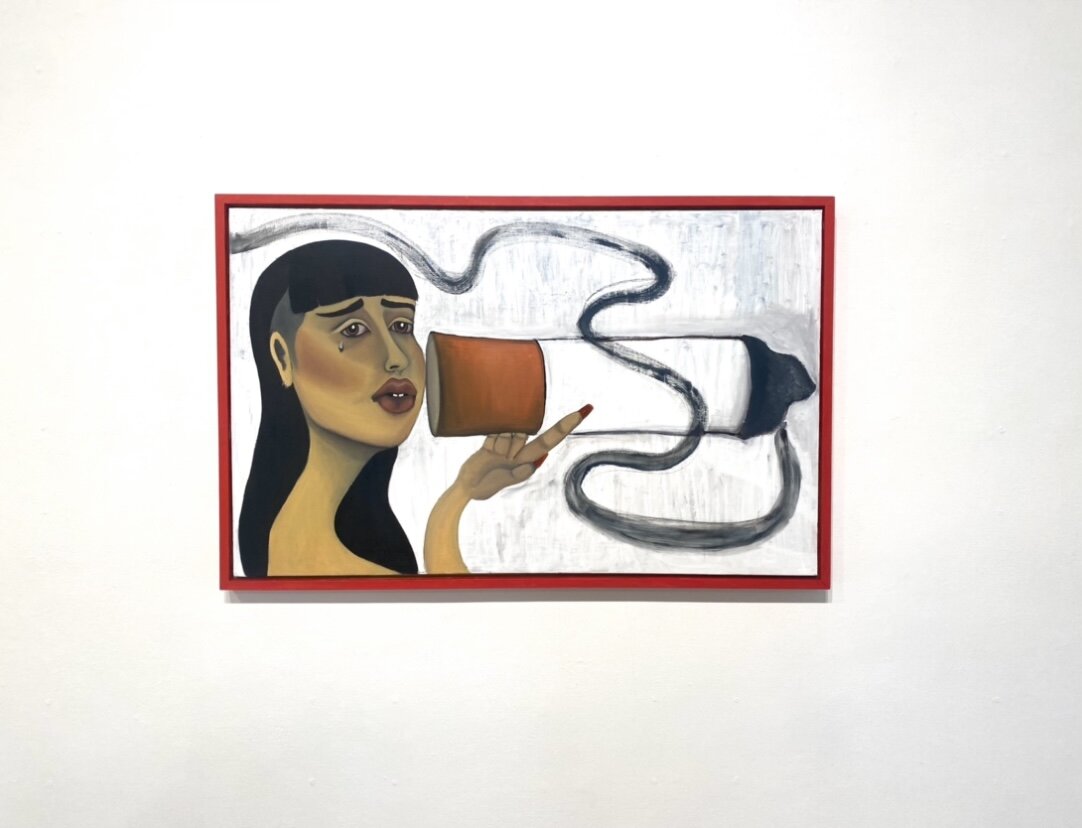

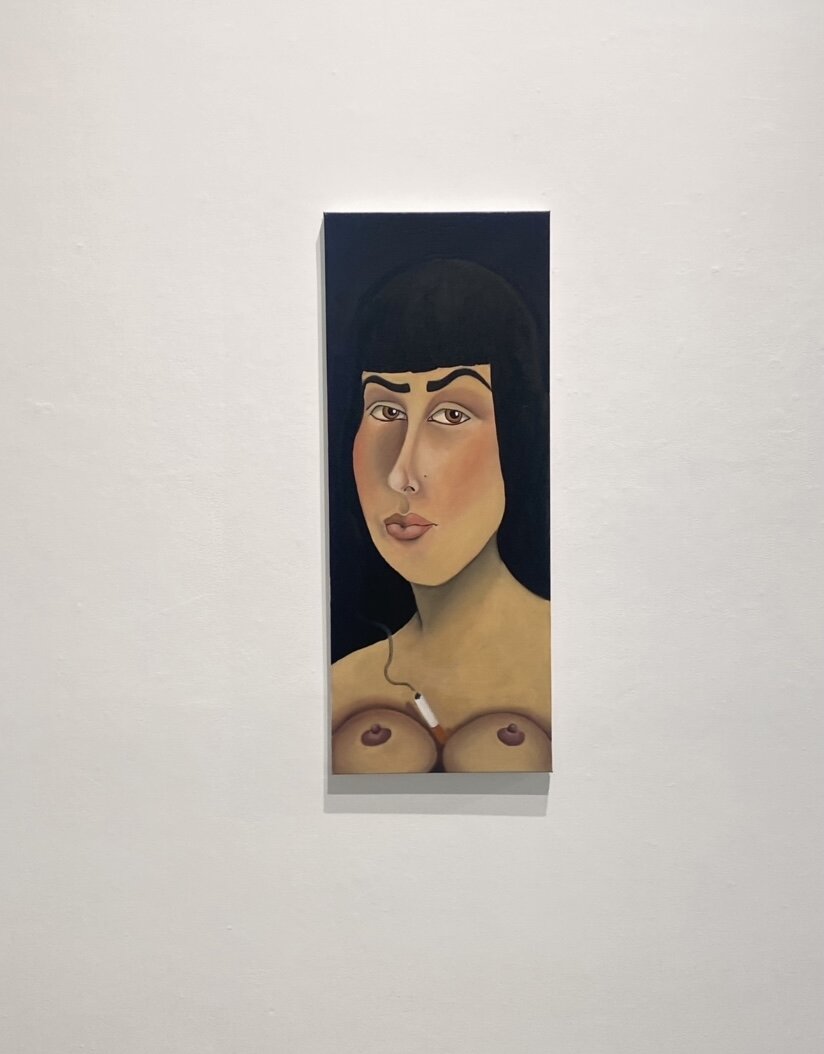

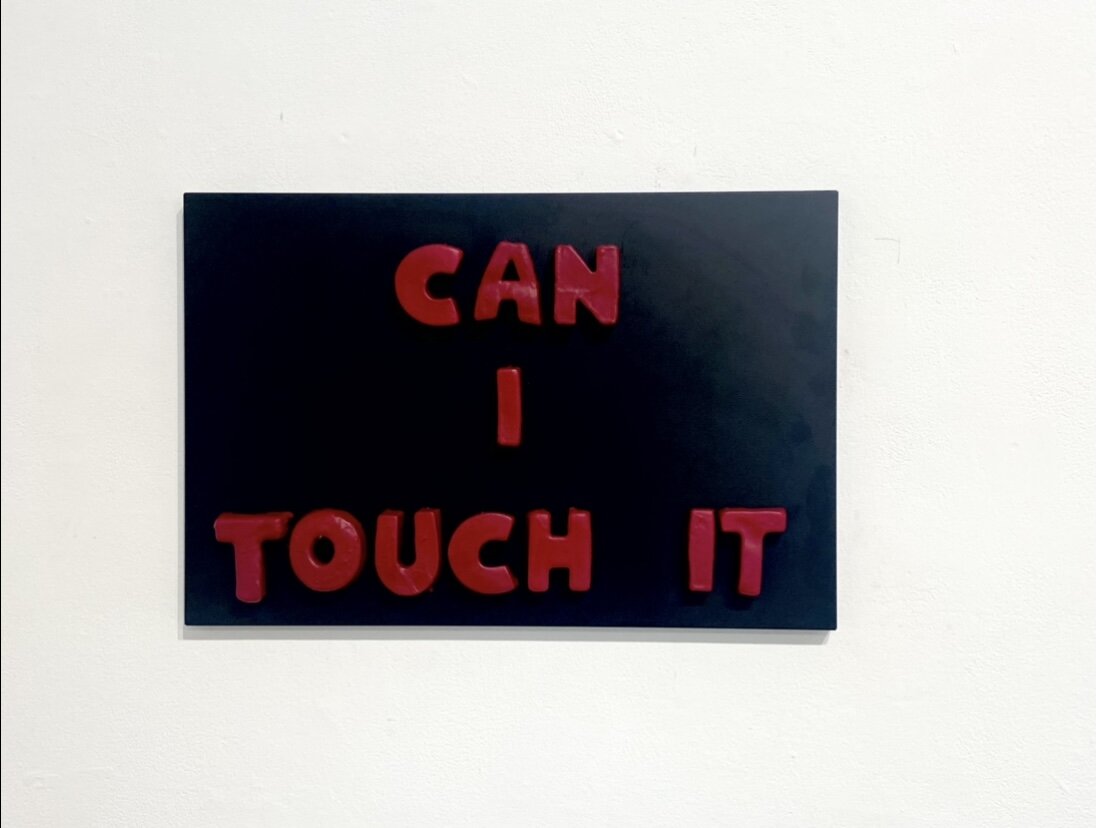

What if you could step back into the womb, walking between the legs of a sculpture depicting the body of a woman? Forget the male gaze’, this sculpture didn’t care about anyone’s gaze at all. Instead, it forced those who were curious to confront the female form on their own terms, unapologetically turning centuries of objectification into an act of defiance and participation. It’s was not here to please, it was created to challenge.

Saint Phalle’s She was not meant to be only observed; it demanded participation. Imagine stepping through that entrance, past your hesitation, into a space that is both obscure and strangely familiar. What would you feel, amusement, unease, or awe? By compelling viewers to enter and explore, Saint Phalle made each participant a co-creator of the experience, a willing participant in challenging how we interact with the female form. Bright and exaggerated on the outside, dark and complex within, the piece turned viewers into co-conspirators. Was the door through her legs a celebration of the body or a deliberate provocation aimed at challenging the gaze? Perhaps both. Saint Phalle was acutely aware of the tension she was inviting. By forcing viewers to enter through such an audacious threshold, she laid bare how we consume bodies, both literally and metaphorically.

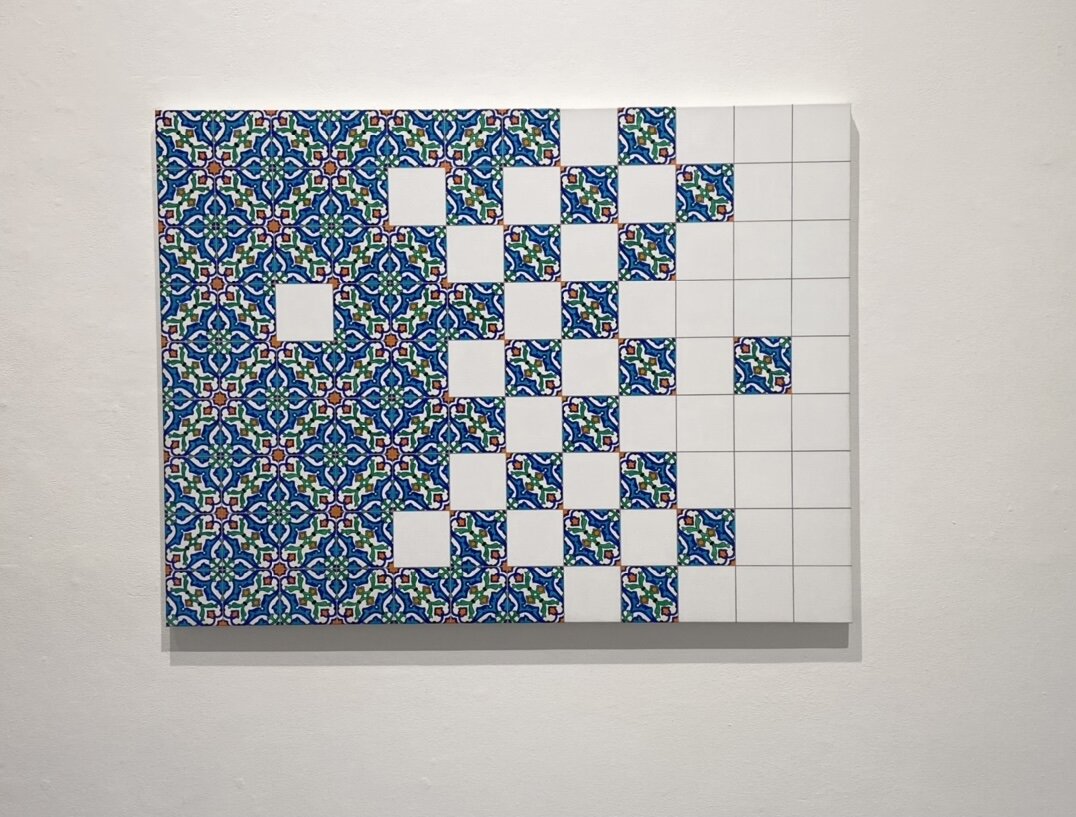

Today, with debates over reproductive rights, gender expression, and bodily autonomy dominating global discourse, She A Cathedral feels eerily prescient. Recent executive orders under the new administration, aimed at protecting LGBTQ+ rights, expanding access to reproductive healthcare, and promoting gender equity, have reignited these critical conversations. These measures underscore the continued struggle over who controls the body, revealing a landscape where progress is often met with resistance. Saint Phalle’s audacious work serves as a poignant reminder of how art can confront these issues, transforming political and cultural battles into visceral, participatory experiences.

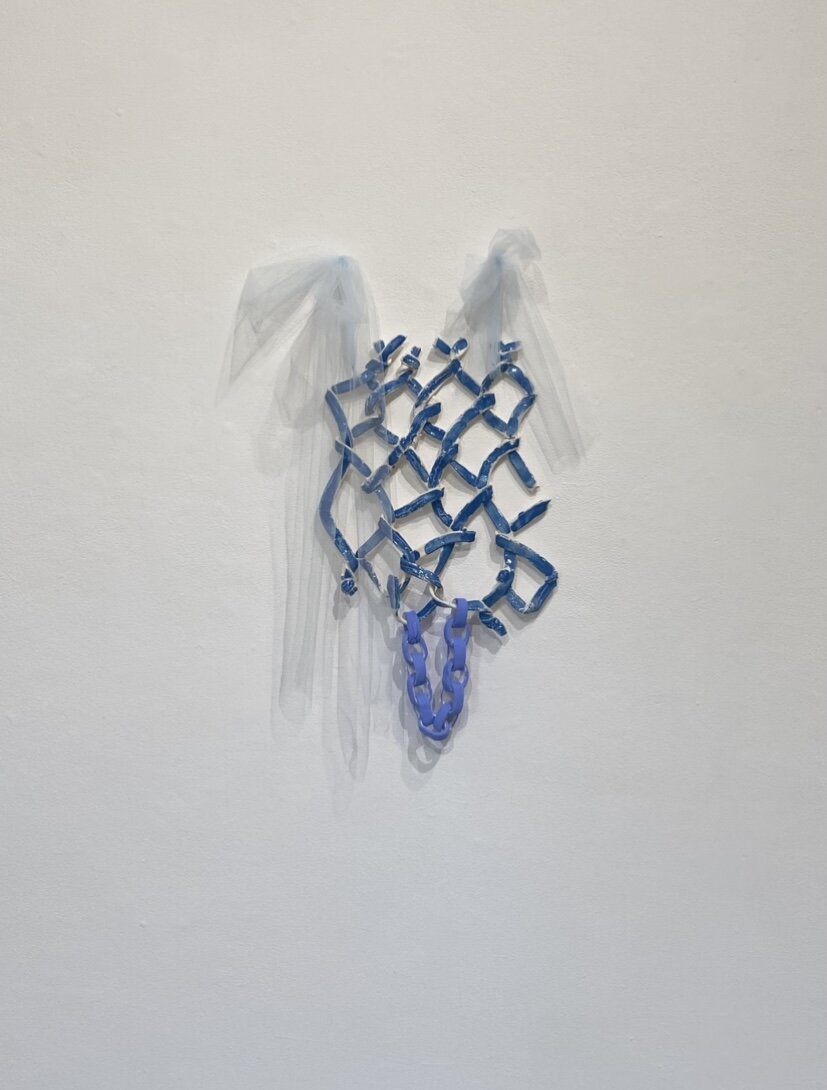

This is where Saint Phalle’s legacy offers not just inspiration but a challenge: how do feminist artists today take her work further? Could artists like Kara Walker, with her haunting silhouettes exploring race and history, or Tschabalala Self, whose vibrant collages celebrate the multiplicity of Black womanhood, build a new kind of cathedral? Could someone like Cassils, whose work interrogates the trans body as both a site of strength and vulnerability, expand Saint Phalle’s vision? The challenge is not to replicate She, but to reimagine it for a world grappling with deeper intersections of identity and power.

Could a new cathedral of bodies also reflect the influence of contemporary political leadership? Under the current administration, executive orders addressing systemic inequities and advocating for greater inclusivity invite us to reimagine the body not only as a site of struggle but also as a space of possibility. Feminist art has long mirrored society’s shifts, both progressive and regressive. Today, it has the potential to amplify these legislative advances, creating spaces that embody liberation, resilience, and transformation. In doing so, it can honor Saint Phalle’s legacy while charting new ground for a world grappling with deeper intersections of identity, power, and representation.

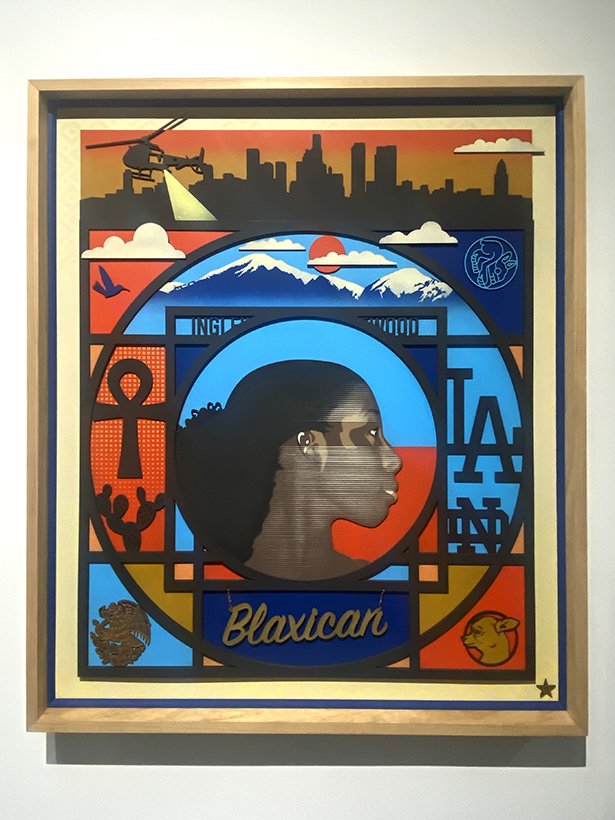

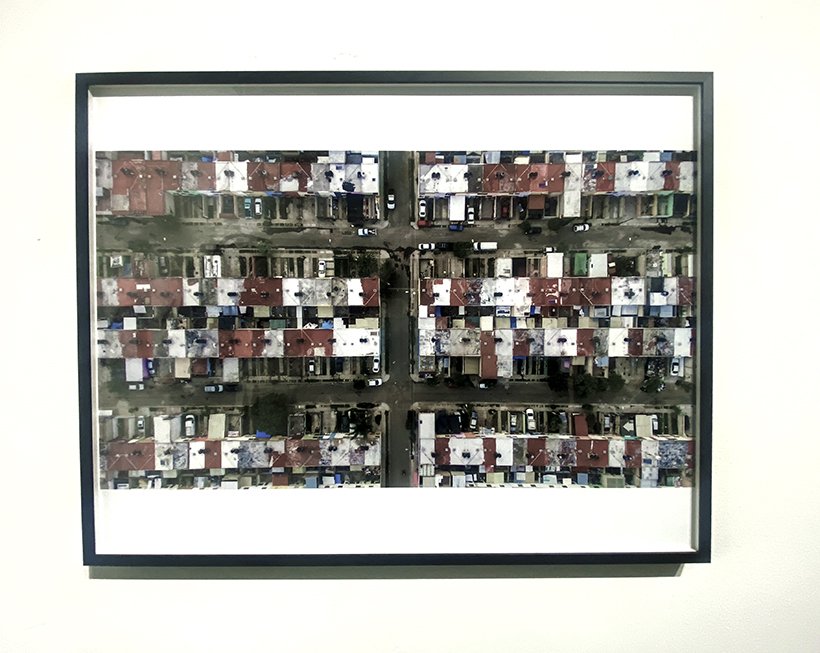

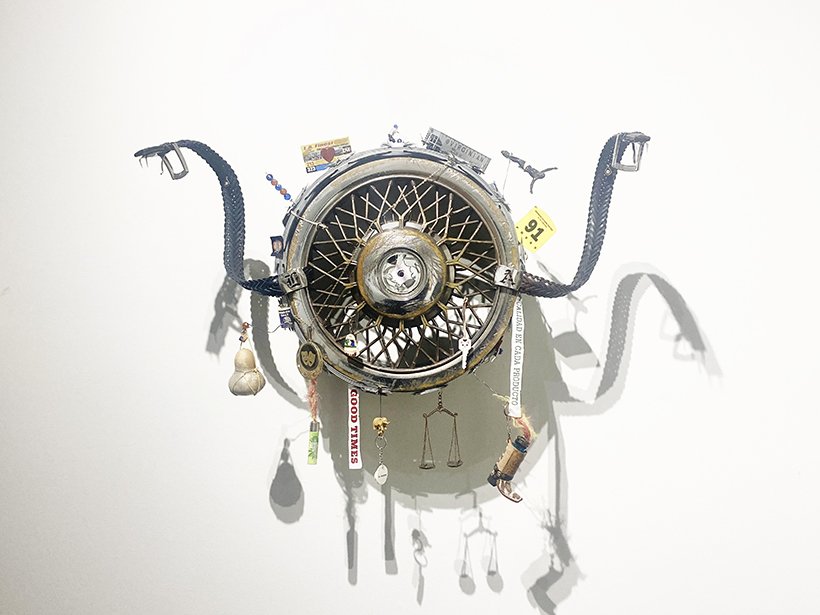

She – A Cathedral was monumental, but it spoke from a particular moment, one shaped by the emerging second-wave feminism of the 1960s. In the 2020s, the question of representation has deepened. What would a new cathedral of bodies look like if it included Black women, Latinas, Latinx, trans and nonbinary individuals, those whose experiences are often marginalized, even in feminist spaces? Could it hold the scars of history and labor alongside the beauty of liberation? Would it provoke as She did, or would it push us further, demanding a reckoning not just with gender, but with race, class, and identity?

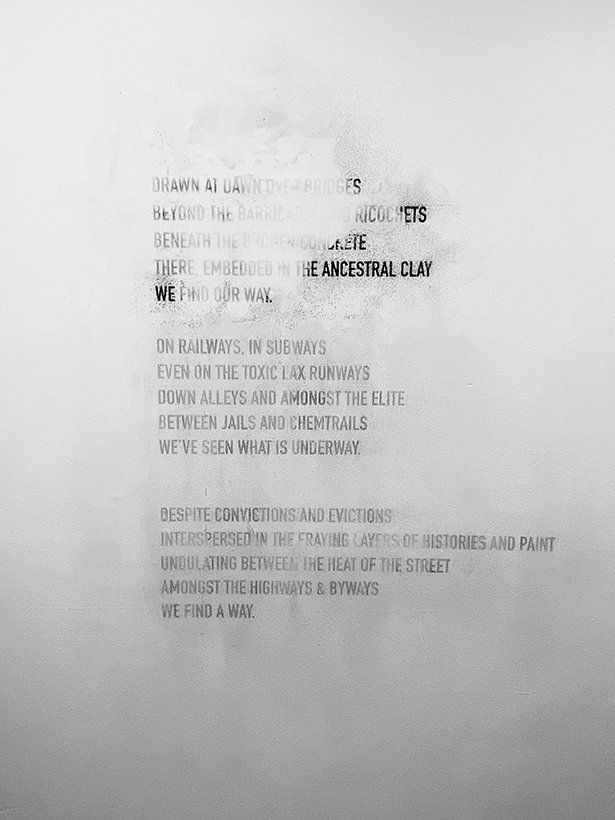

Saint Phalle’s She anticipated today’s immersive art installations, but its power lies in what it asked of its viewers: to step beyond the passive consumption of spectacle and engage with discomfort, complexity, and intimacy. Today’s immersive works, while dazzling and often technologically sophisticated, can sometimes dilute this level of challenge, leaning heavily on aesthetic allure over introspection. However, others expand on her vision, layering interactivity with deeply personal or political narratives. Saint Phalle’s legacy asks us to consider: are we still engaging with art that makes us question, or are we settling for art that simply entertains? Unlike the spectacle-driven Instagram able works of today, She insisted on engagement, discomfort, and introspection. It wasn’t designed to be a passive experience; it was messy, physical, and deeply human. To honor that legacy, any modern interpretation must do the same—not by replicating its form, but by expanding its scope. A new cathedral must reflect the kaleidoscopic realities of bodies today, asking viewers not just to see, but to feel and question.

Art at its best challenges us not only to look outward but inward, daring us to confront the unspoken, the unresolved, and the deeply personal. It demands not just observation but participation in the truths it reveals, truths about ourselves, about the world, and about the bodies we inhabit and often take for granted. Who will take up Saint Phalle’s mantle? Who will create the next unapologetic celebration of the body, not just as a site of beauty, but as a battleground, a refuge, and a force of transformation? The body remains contested terrain. And the question lingers: who will dare to build the next cathedral?

Julian Lucas, is a photographer, a purveyor of books, and writer, but mostly a photographer. Don’t ever ask him to take photos of weddings or quinceaneras, because he will charge you a ton of money.