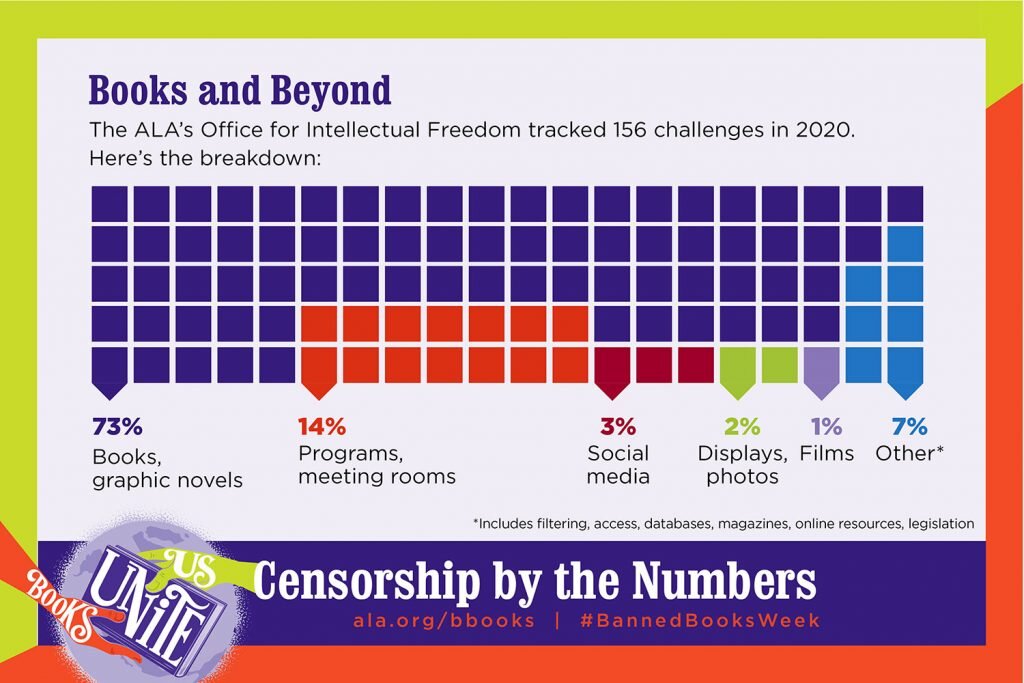

Books can connect us culturally regardless of gender race or economic status. As an advocate for storytelling through all mediums of art, including photography, in addition to being an outspoken critic of censorship, I am happy to present a list of this years banned, censored or challenged books.

Banned Books Week is an annual celebration of the freedom to read. In 1982, Banned Books Week was created in response to a rise in the number of book challenges in schools, bookstores, and libraries. It is traditionally observed during the last week of September and stresses the significance of free and open access to information. Banned Books Week brings together the whole book community — libraries, booksellers, publishers, journalists, educators, and readers of all types and induces book culture— to advocate for the freedom to explore and express ideas, even if they are deemed unusual or unpopular by some.

At the 1965 American Library Association Midwinter Meeting preconference in Washington, DC, the Intellectual Freedom Committee (IFC) recommended an ALA unit be established to “promote and protect the interests of intellectual freedom.” Among its interim objectives was to create “positive mechanisms” that could defend intellectual freedom, collaborate with state intellectual freedom committees, and establish relationships with other First Amendment groups.

Judith F. Krug was a librarian, freedom of speech proponent, and critic of censorship. Krug became director of the Office for Intellectual Freedom at the American Library Associationin 1967. In 1969, she joined the Freedom to Read Foundation as its executive director. Krug co-founded Banned Books Week in 1982. Watch this video of Krug talking about intellectual freedom in 2002. National Council of Teachers of English

Banned Books Week Sept 26th - Oct 2nd

Book Titles within the 10 Most Challenged Books of 2021

“Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You” by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi

Reasons: Banned and challenged because of author’s public statements, and because of claims that the book contains “selective storytelling incidents” and does not encompass racism against all people.

“George” by Alex Gino

Reasons: Challenged, banned, and restricted for LGBTQIA+ content, conflicting with a religious viewpoint, and not reflecting “the values of our community”.

“Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story about Racial Injustice” by Marianne Celano, Marietta Collins, and Ann Hazzard

Reasons: Challenged for “divisive language” and because it was thought to promote anti-police views

“All American Boys” by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely

Reasons: Banned and challenged for profanity, drug use, and alcoholism, and because it was thought to promote anti-police views, contain divisive topics, and be “too much of a sensitive matter right now”

“Of Mice and Men” by John Steinbeck

Reasons: Banned and challenged for racial slurs and racist stereotypes, and their negative effect on students.

“Speak” by Laurie Halse Anderson

Reasons: Banned, challenged, and restricted because it was thought to contain a political viewpoint and it was claimed to be biased against male students, and for the novel’s inclusion of rape and profanity.

“To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee

Reasons: Banned and challenged for racial slurs and their negative effect on students, featuring a “white savior” character, and its perception of the Black experience.

“The Hate You Give” by Angie Thomas

Reasons: Challenged for profanity, and it was thought to promote an anti-police message.

“The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison “Speak” by Laurie Halse Anderson

Reasons: Banned and challenged because it was considered sexually explicit and depicts child sexual abuse.

“The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian” by Sherman Alexie

Reasons: Banned and challenged for profanity, sexual references, and allegations of sexual misconduct by the author.

Julian Lucas, is fine art photographer, photojournalist, and creative strategist. Julian also works as a housing specialist which, includes linking homeless veterans to housing. Julian has lived in Chicago, Inglewood, Portland, and the suburbs of Los Angeles County including Pomona.