My Ego Confuses My Heart - Joel Rhymer

ARTIST

Joel Rhymer

ARTIST WEBSITE

Joel Rhymer

LOCATION

Freedom, NH

My Ego Confuses My Heart

At first look, most people would call these pictures “street photography” – candid scenes of day-to-day life. They would be correct.

In many ways though, I consider them to be “anti-street.”

Let me explain.

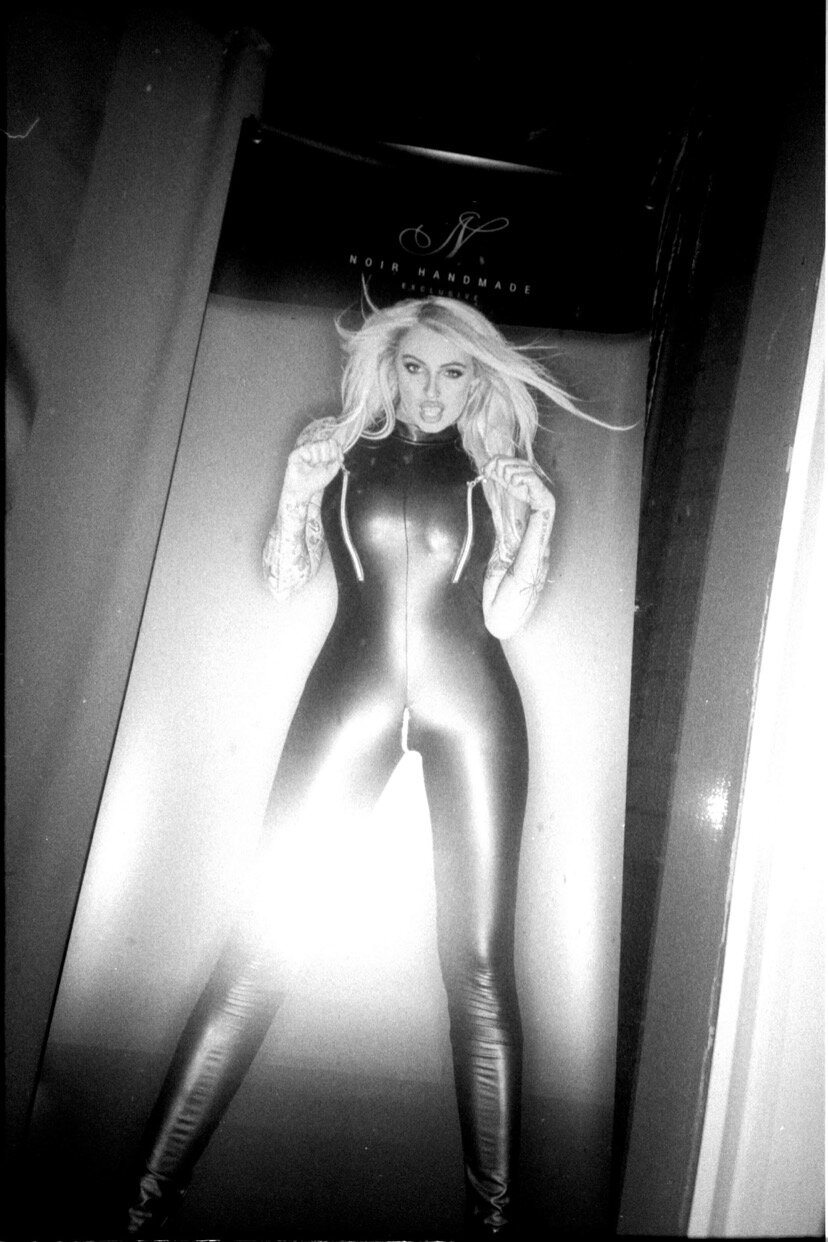

While I love the energy and chaos of the internet, it seems that much of what passes for street photography in contemporary times are countless hurried and random shots of strangers filling up my social media feeds. It’s a firehose of pained expressions on passersby shot from the hip, contorted bodies, bright flashes in the face, women in revealing clothes, disadvantaged persons without defense, or faceless silhouettes in cold shadows. It seems rushed, derivative, and, at times, aggressive.

Those particular photos often say more about the photographer’s skills as a camera-based predator and the technical qualities of their equipment. The photographer’s name and personality become the subject of attention, and the person being photographed seems to be little more than an object fetishized or exploited in return for likes or follows from a madly scrolling public.

There’s another way. It involves photographing from the heart, and not the head. While my photographs have street qualities, they are not simply unplanned and accidental candids. There’s some modest intention I believe.

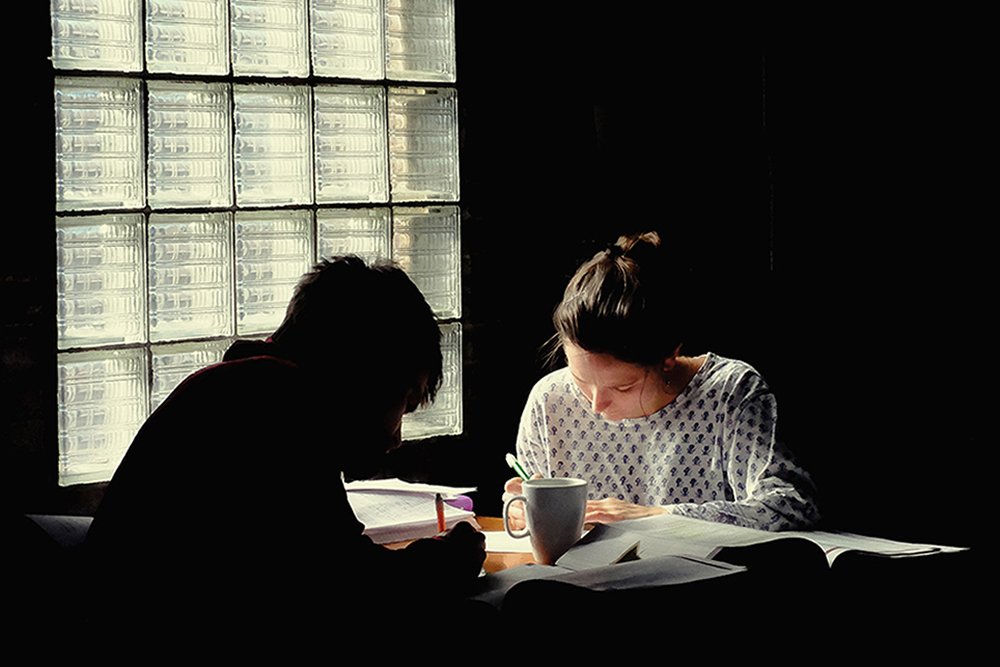

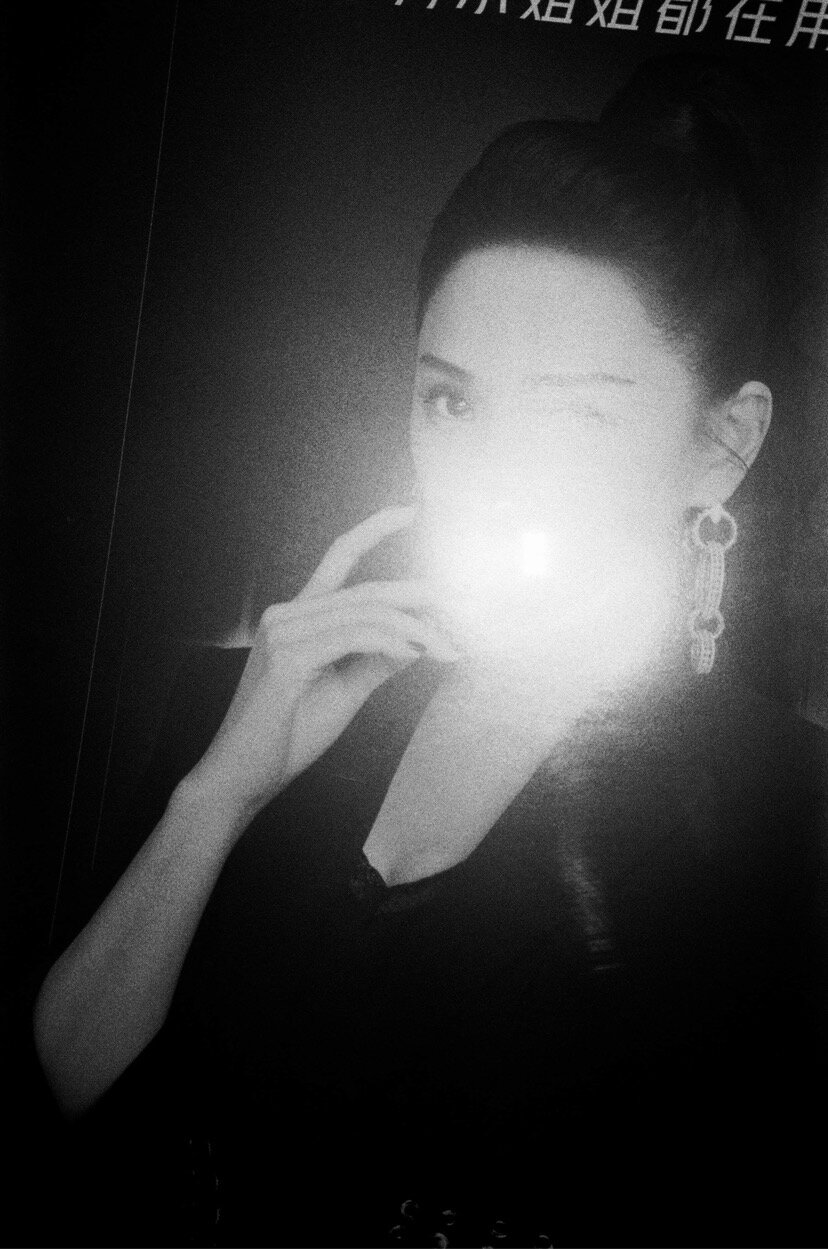

In a 2016 New Yorker magazine piece titled “Loneliness Belongs to the Photographer,” Hanya Yanagihara describes the act of bearing gentle and silent witness with a camera. It’s when the photographer willingly and deliberately makes theirself anonymous in order to give visibility to an otherwise overlooked instance in another life.

In other words, a simple and uncomplicated moment in one person’s life becomes recognized as something valuable because the photographer says, “Don’t think about me. Look instead at how fleeting and beautiful life is.”

Names and personalities are irrelevant. Human connection becomes more important...the story and the moment, the common emotion, the shared light.

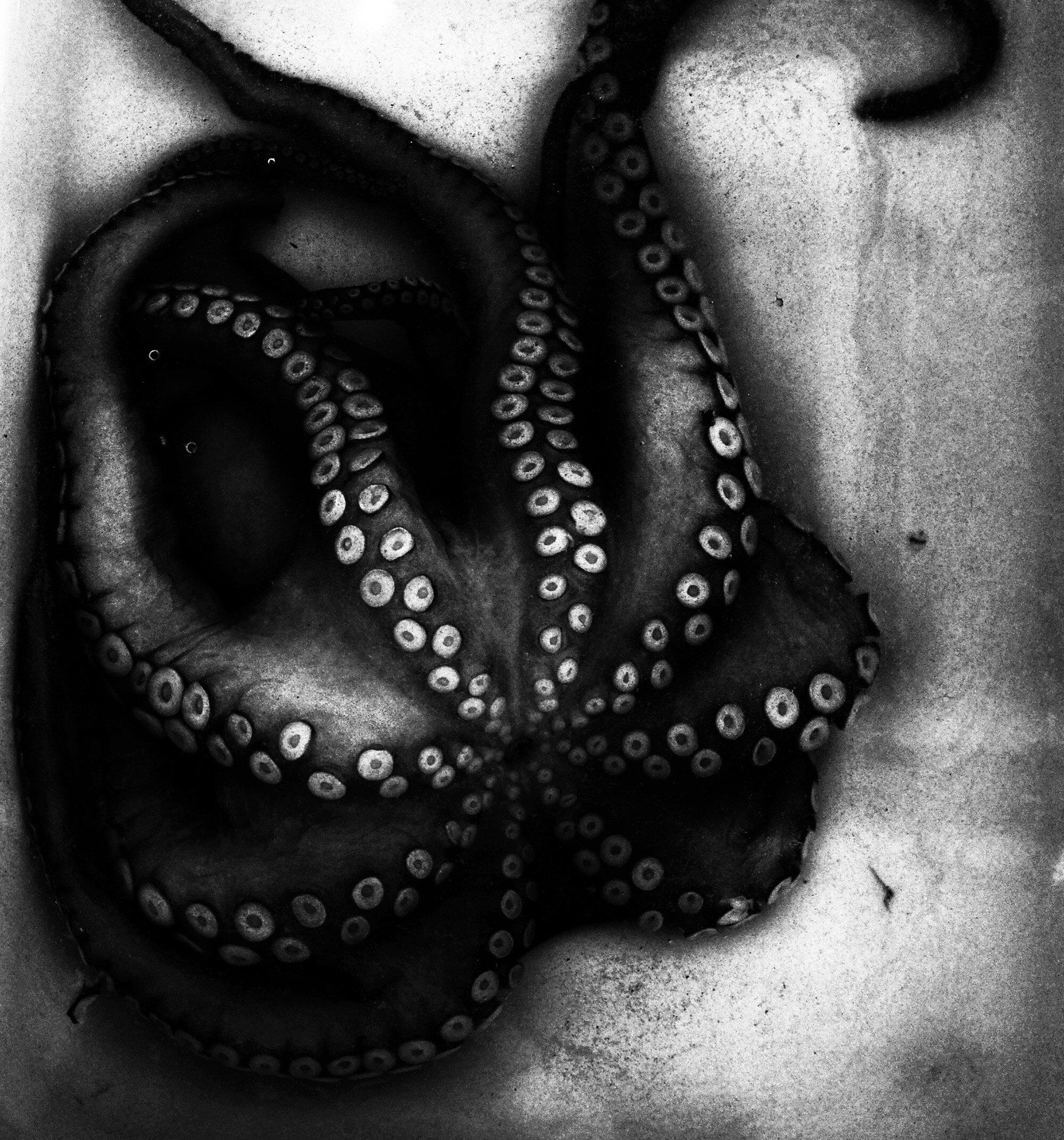

I especially appreciate photos that seem a little uncertain. Such works require the viewer to pause, to see more thoughtfully, to open up, and to become invested before fully understanding. Ego and aggression are forgotten, and in the space, between seeing and knowing, feeling and empathy flow in. At least for a moment, you are not alone.

Someone once told me, “I can’t look at your photos too long. They make me think too much.” I took that as a compliment.

These photographs represent a 10-year period of time out there in the world. Some deal with individuals in public places. Some show a unique moment or quality of light. In a few, I see humor. In others, the subject is lost in their own world, and I, as the photographer, feel a little lost as well. For me, there’s comfort in returning to the same subway platforms, bus stops, and street corners months or years later. Familiar ground. It’s not a surprise to me if a photograph leads to a conversation, and a stranger becomes a friend.

Most of the time, I see individuals rather than wider scenes. If it tells the story for me, I may crop a photo down to only one subject. It may be a doorman waiting solemnly outside a Texas theater where a benefit for shooting victims is taking place. Perhaps it’s a young couple, looking a little downtrodden, seeking shelter from the cold pouring rain at dawn. It may be a girl in a subway car texting someone she loves.

In any case, I like to believe that despite all the alienation one often feels in our modern world, we can still maintain some sort of connection by noticing one another. What a privilege it can be to look, and look again. On se pose et on regarde nouveau...

To me, a successful photograph is an act of love.

Joel Rhymer’s professional career has always been about experience and its interpretation. For nearly 40 years, he worked as a high school biology teacher, a naturalist in some wild and beautiful places, an executive director with important responsibilities, a scientist, and an environmental educator with significant stories to tell. Photographs were his way to connect with

learners and promote his work.

Over time, however, he began to see photography as an artform instead of just a tool. He wanted the ability to create a photograph with intention - not just photos that simply did a job - something that expressed a deeper and more personal experience. So he quit full-time work at the age of 58 to spend more time with his camera.

Joel and his wife, Elizabeth, live in the quaint New England village of Freedom, NH. They’ve been married for 37 years, and have two grown daughters. He’s had numerous photos published in various places, and many selected for exhibitions across the country. Several of his works are in private collections, and he’s active in a small gallery in his town. He also presents workshops that draw upon not only his photography experience but also a lifetime of teaching others.